UPDATE — SEPTEMBR 1, 2023: VICTORY! Kanaloa Octopus Farm’s location near Kona on the Big Island has permanently closed! The state of Hawaii has decided not to renew Kanaloa’s lease after months of pressure from animal activists, media exposure, and even a complaint led by Harvard Law School in the wake of our investigation exposing the facility as little more than a petting zoo that collected tourists’ dollars to fund the creation of an octopus factory farming industry. Read on for the groundbreaking exposé that led to this triumph for octopuses everywhere.

UPDATE — JANUARY 28, 2023: Late last year, I published the below investigation into Kanaloa Octopus Farm on the Big Island of Hawaii, which captures wild Hawaiian day octopuses, entrapping them in tiny, isolated tanks and subjecting them to breeding experiments under the guise of “conservation.” This week, the Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources issued a cease-and-desist letter to Kanaloa for operating without required permits. Owner Jake Conroy has reportedly claimed that these octopuses were not captured in West Hawaii waters—in direct conflict with what I was told on my tour: that Kanaloa pays someone to capture octopuses off-shore. My investigation revealed that, funding itself through petting zoo-like tours and state support, the facility has attempted to breed hundreds of these octopuses, a process that’s always fatal—but as of 2022, babies had only survived up to 13 days. Despite Kanaloa’s public claims that it isn’t interested in farming, government records show plans for supplying octopus and squid to the restaurant industry. For now, the octopus program has been temporarily shut down, and Kanaloa is shifting to bobtail squids, a species it is already profiting off of through breeding and selling (and for which there is insufficient data for Kanaloa to claim they are doing so in the name of conservation).

- Watch my video update on Instagram

- Download photos/videos from the investigation at We Animals

- Check out our media coverage: Hawaii News Now | Big Island Now | Kaua’i Now | Feature Shoot | Vice News Docs | Sentient Media (2) | Conversations with Animals Podcast | Species Unite Podcast | Washington Times | Daily Hive | Our Hen House | We Animals Media | Plant Based News

FULL INVESTIGATIVE STORY BELOW

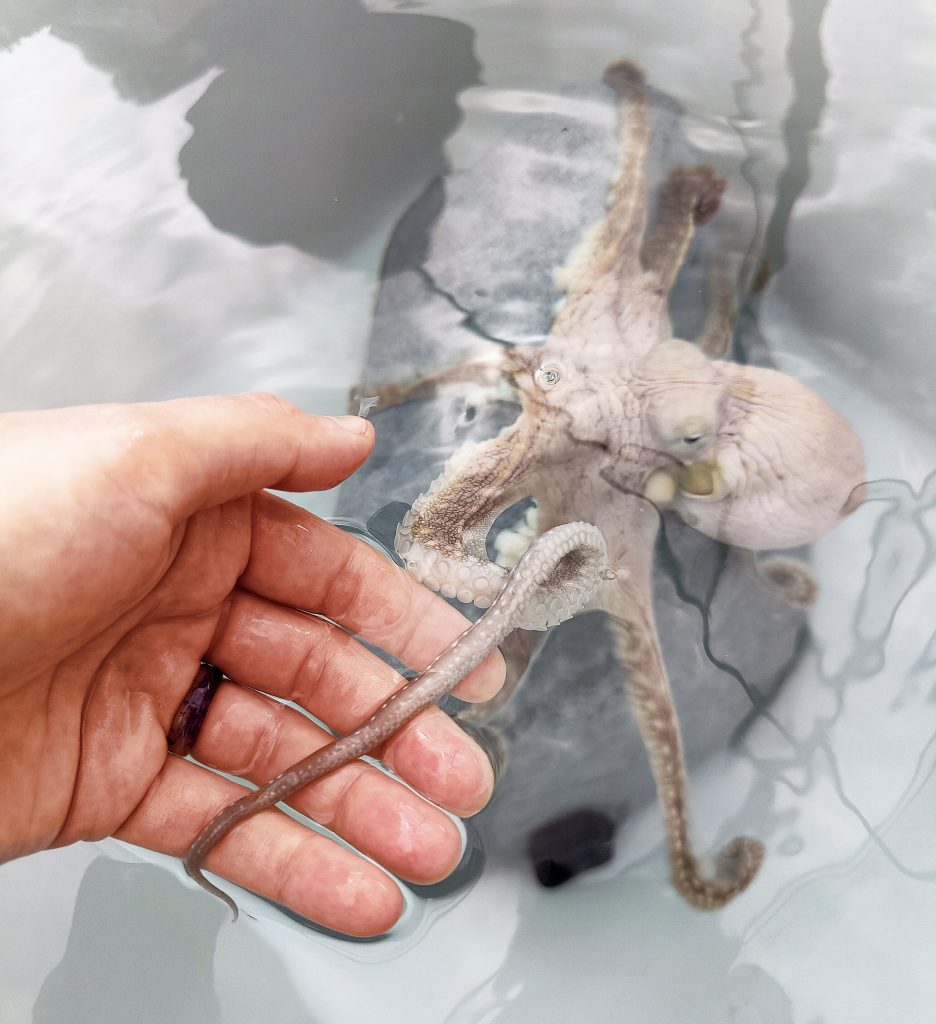

(October 9, 2022) I stood under the blazing Hawaiian sun, gazing out at the ocean while imagining myself diving in, dancing among the fish, and extending a friendly finger (à la E.T.) to a curious cephalopod—just like the protagonist of My Octopus Teacher had done before me. Instead, I snapped back into reality and glanced down at several rows of white boxes filled with water and lined at their upper edges by spiky green Astroturf. I gingerly plucked off a row of suction cups that had been ascending my forearm, sending their owner, a Hawaiian day octopus, or heʻe mauli, gliding back down into her home, one of those white boxes—no bigger than a bathtub.

I’d always thought my first real encounter with an octopus would occur on their terms, out in the open sea. But when I heard about the 73-million-dollar forthcoming octopus farm that’s making waves in the Canary Islands—and then learned that there was already a dollhouse-sized version of one on the Big Island my family calls home—I knew I had to go. I had to see the reality behind Kanaloa Octopus Farm’s claims on its website, like that it’s “committed to developing green bio-technologies that decrease our demand for ocean resources,” and find out whether they really held water.

On the surface, the small facility on Hawaii’s Kona coast that I visited this past spring seemed akin to a petting zoo of the sea. An exuberant tour guide instructed us to wash our hands and led us over to the small collection of tanks, each holding an individual octopus, who was barred from leaving—as octopuses are wont to do (recall, for instance, Inky, an octopus who slid out of her tank at a New Zealand aquarium, down a drainpipe, and back into the ocean several years ago)—by the aforementioned strips of Astroturf. Guests plunged their hands into the tanks and wriggled their fingers, and one by one, the octopuses emerged from their hideaways to examine the intruders. Attaching their arms to our fingers and wrists, eliciting shrieks of joy from the guests, they used their suckers to taste, smell, and feel us.

Useful appendages—those eight, self-regenerating arms lined with a collective 2,240 suction cups, which help them not only sense their environments, but climb any surface; use tools (like those who hide themselves tightly inside shells like armor, not just in response to danger, but in preparation for future danger); and even ride on a befuddled shark’s back to escape hungry jaws. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. These cephalopods have also been documented opening and closing jars, squeezing through the tiniest cracks to climb a flight of stairs culminating in the kitchen, retrieving lobsters from nearby tanks, changing colors while dreaming in a state similar to REM sleep in humans, and recognizing and holding grudges against a specific researcher (evidenced by their repeated spraying of water at said researcher).

Yet we often find ourselves relying on rudimentary, anthropocentric measures of intelligence to define our spheres of moral consideration, like the so-called “mirror test,” or the ability of animals to recognize their own appearance in a mirror—as though such a device would be of any use to an otherworldly animal who can camouflage herself and disappear into her environment in an instant by shifting her coloration. (Meanwhile, Homo sapiens is relegated to fantasizing about magical Invisibility Cloaks in literature, or investing billions of dollars into developing technologies these animals are simply born with. But, if I must play along, octopuses have indeed taught themselves how to engage “correctly” with a mirror—they enjoy grooming themselves and using it to spot crabs to feast on.)

Ponders Erin Anderssen in a recent thought piece in The Globe and Mail, “Should we assume dominion over an exceptional brain that developed parallel to our own, in a foreign place and against the odds? Do we too often assume that thinking differently means thinking less?”

With the Canary Islands’ massive commercial operation looming on the horizon, projected to kill nearly 300,000 octopuses per year, animal activists worldwide are responding with a resounding “no!”—and fervently campaigning to stop the project through petitions, protests, conferences, tweetstorms, and more. These marine advocates are reminding decisionmakers that we’re only on the cusp of grasping the remarkable capabilities of these alien-like beings, who thrive in their own underwater realms—and that factory farming them will be among this century’s greatest perils inflicted by humanity on sea life.

Has the ship already sailed on thwarting the creation of this entirely new industry? Already, octopus farming—the latest iteration of the 20th century’s destructive brainchild, industrial animal agriculture—has attracted tens of millions in investments, outwardly in the name of reducing pressures on wild octopus populations (while apparently the notion of shifting demand away from these sea beings altogether didn’t seem quite so profitable to said investors). So, to hell with the myriad environmental consequences of aquaculture, such as nitrogen and phosphorous pollution, antibiotic misuse, and, perhaps the linchpin of them all: octopuses are carnivores, eating two to three times their own weight. As such, their captive production will increase pressures on other fisheries—either wild or farmed—to sustain them. According to a Compassion in World Farming (CIWF) report, “[O]ctopus farming would contribute to further food security issues in regions such as West Africa, Southeast Asia and South America where the main industrial fishmeal factories are located.” Facing such a dire picture, activists aren’t relenting in their upstream fight.

But what does a gigantic forthcoming factory farm across the globe have to do with the seemingly innocuous octopus playground in Hawaii, where I stood flanked by tourists gawking over a dozen or so of these creatures playfully throwing rubber duckies? I listened to our guide, clearly enamored by cephalopods herself, extoll their virtues and spout off their individual names and favorite toys. She spoke of how Kanaloa Octopus Farm was not actually a farm at all, but a research facility developed with conservation in mind, just like the website had told me. They did not raise octopuses for consumption, she declared repeatedly throughout the hour.

It would have been easy to grab an octo-plush from the gift store and stroll off to lunch at one of Kona’s oceanside eateries, where I could then type up a Google review over a frozen açaí bowl about how cute and curious and fun those Kanaloa octopuses were, just as hundreds or thousands of visitors before me have done. But something unsettling was washing over me as the tour neared its end.

I couldn’t count how many utterances of the word “conservation” I’d heard, and seen, that day (if only I had a nickel for every time…). So I approached the guide and asked what this meant—what, precisely, was their plan? Were these octopuses endangered?

No, she replied, not in Hawaii, but in other parts of the world, where demand for octopus meat has surged. Kanaloa, though, hoped that through successful research, they could share their findings on breeding octopuses with other countries. All in the name of “replenishing the natural population,” she told me.

Essentially, Hawaii’s octopus farm intended to teach their breeding strategies to other countries, which could then turn around to farm octopuses for food and reduce their own reliance on wild-caught populations. Ah, well, we mustn’t kill the messenger, right?

But I was left wondering: could Kanaloa really be a neutral middleman, laboring all for the good of Planet Earth—or did it stand to benefit from the fruits of its labor? At the time of my visit in March 2022, Kanaloa’s claim-to-fame was that it had gotten the furthest in closing the octopus life cycle by rearing babies to a mere 13 days of age before die-off. According to our guide, “no single person” has ever been able to raise an octopus from baby to adulthood. It seems, though, that Kanaloa staff is overstating their two-week milestone, achieved only with a single species, Hawaii’s day octopus: After all, the Nueva Pescanova Group, the corporation behind the upcoming Canary Islands facility, had successfully bred and reared common octopus, or Octopus vulgaris, larvae to adults by 2019. If that’s the case, perhaps Kanaloa is looking forward to playing a foundational role in a separate, future day octopus farming industry, piggybacking off the lessons of its Spanish predecessor. After all, it’s a vast ocean out there, with plenty of species for every ambitious capitalist to, well, capitalize on.

On Facebook, Kanaloa touts that it “strive[s] to produce a sustainable alternative to wild caught octopus for aquariums, researchers and saltwater aquarium hobbyists,” but by the end of my visit, I already knew this didn’t encompass the full scope of its aims. So, while bedridden with COVID this spring and finally exhausted after days of 18-hour-long sleeps, one night I dove down an internet black hole ‘til sunrise (as one does) to get to the bottom of it all.

Like most small businesses, Kanaloa Octopus Farm’s beginnings in 2015 were meager, with founder and impassioned researcher Jake Conroy sinking his own savings into the commercial aquaculture project after witnessing the cashflow challenges scientific research typically faces. The “petting zoo” front seemed a promising way to fund his altruistic vision at the time, keeping the lights on and the water flowing. He consistently explained in interviews that his plans did not include farming octopus for food, but only gifting the world the tool of breeding octopuses to help wild species survive.

The man was, overtly, a true animal lover. To National Geographic, Conroy declared, “Nine times out of ten we wind up convincing people not to eat octopus. … We’re fine with that.” And in another interview, Conroy explained that the octopuses at Kanaloa were purchased from fishermen who would have used them for bait. “We call them our rescue animals. … Their fate is a little better than what it was.” (Today, according to our tour guide, the farm has graduated to hiring its own octopus-catcher.) But in that same interview, Hawaii Magazine reported that the “goal of Kanaloa is to someday create a viable and sustainable on-land octopus farm.” And to a Hawaiian food writer, Conroy described selling octopus to local restaurants as a “pie-in-the-sky dream” of his.

Then, in the fall of 2021, as the aforementioned CIWF report condemned the budding octopus farming industry and accused Kanaloa of harvesting young octopuses to fatten them up in tanks, Conroy fired back: “They’re claiming we’re the only octopus farm in the U.S. and that’s not true — there are no octopus farms in the U.S. … We market ourselves as an octopus farm, it’s a fun thing for tourists to hear, but we’re not farming anything for meat.”

That month he also appeared on Hawaii Public Radio and launched into a slew of defenses, first by downplaying octopus intelligence (“I don’t see a lot of evidence of them being more intelligent,” said Conroy, while accusing activists of anthropomorphizing the animals—a bold claim from a businessowner whose captives are endowed with names like Stretch and Shrek). Then, he cast doubt on the economic viability of pursuing octopus farming (I know some Spanish executives who’d beg to differ), as though hoping to quietly excuse himself from this fight and swim back under the radar. Had Conroy already forgotten his 2019 remarks about his plans to scale up to become an exclusive supplier of octopus to Hawaii’s gourmet restaurants?

Kanaloa’s inconsistencies and flip-flopping are arguably a simple battle over semantics, or perhaps over its present and future. But public records and currency flows don’t lie, so I dug deeper. I discovered that Kanaloa was founded as a partnership between both a non-profit research foundation and a for-profit company, Fatfish Farms, LLC, operating off its ticket sales. Through tours, the business grew its revenue by 273 percent over just two years, landing it recognition as Hawaii’s 5th fastest growing company. The first red flag I uncovered was a revelation in 2018 by Environment Hawaii that as a tenants of the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Authority (NELHA), the rapidly growing for-profit arm of Kanaloa Octopus Farm, “like all other tenants of state-owned lands, [should be] expected to pay property taxes based on the assessed value of the land and improvements they occupy,” yet as an occupant of NELHA’s “research campus,” the farm has never been billed. The executive director of NELHA at the time claimed that such “pre-commercial or research projects” are “considered short-term,” but there’s no end in sight for Kanaloa. The company has not only been granted a front-row, tax-free plot of land, but also its own supply of deep-sea water channeled up by NELHA from 3,000 feet below sea level to be distributed at a rate of up to 100,000 gallons per minute throughout the state-funded (to the tune of $130 million) research park.

And then, buried in 2019 NELHA meeting minutes, I stumbled upon an expansion proposal from Kanaloa which, though eventually sidelined by the pandemic, was telling. Planned growth areas included not only research, but also “ink for food products, ornamental trade and octopus meat for local restaurants,” accompanied by the note: “see confidential proposal in Attachment 3.” (I’ve yet to obtain the full proposal.) Further, the document revealed that Kanaloa had already begun selling aquaculture products the prior year—not from octopuses, but from bobtail squids, whom they’d apparently already successfully bred. “If Kanaloa starts selling [bobtail squids] in mass [sic],” it read, “they would be the only supplier in the world.” And although publicly describing itself as fully funded by its tours, Kanaloa claimed in its proposal that it had secured over $600 thousand from investors, including Marissa Meyer, former CEO of Yahoo, to pursue its commercial aspirations.

As sunlight began to creep through my bedroom window, interrupting my research frenzy long enough for me to seek out more tissues, I began to reflect on my findings. Could a few tanks on a palm-lined seashore really be as dangerous to cephalopods as the mammoth Canary Islands operation slated to slaughter millions of them within the next several years? I’m sure that Kanaloa will continue to split hairs over its business model and intentions—conservation, partnering with gourmet restaurants, or even entertaining smiling children—but in the early morning haze, it dawned on me that none of that mattered. In the business of raising and killing sea creatures on land, away from their homes, there is no impartial researcher, supplier, or middleman—only individual, critical cogs in the machine.

I realized that, for a wild octopus yearning to stretch her arms beyond impassable blades of Astroturf and glide off into the depths of the Pacific, any farm is a factory farm.

And by positing itself as an octo-friend, a champion of the seas, an environmental savior, Kanaloa obscures its role in building this new industrial machine and setting us on an uncharted course we can’t ever come back from, using a species never before raised entirely in captivity. Its marketing is, then, a greenwashing and humanewashing front to lure in dollars, and support, from captivated tourists who might be otherwise appalled at the colossal venture under construction across the Atlantic.

In the weeks before I visited Kanaloa Octopus Farm, my dad had just returned home to the Big Island from a seven-month-long, gut-wrenching stay in the hospital and a rehabilitation facility in Honolulu after a failed coronary bypass operation nearly killed him. As every single second dragged by, day after day, he was reminded of his predicament, confined to a single bed within a single room. And even as his body progressively healed, his mind, deprived of stimulation and disconnected from the outside world, was stuck in a state of delirium until he finally could return home and reestablish his bearings.

On the farm, as I observed our tour guide scurrying about reminding guests over and over to pry any wandering octopus arms off the top edges of the tanks and return them to their confinement, I recalled the most harrowing part of my dad’s experience, which still haunts him today: month after month, lying there, he was prevented from even touching his toes to the ground before a team of nurses rushed in to hoist them back into bed.

Given the profound anguish that being trapped, with no control over one’s surroundings, provokes, it’s no wonder that octopuses forced into cramped conditions are prone to fighting and cannibalism. In nature, these highly sensitive beings are already extremely particular about their homes and social lives. In two octopus communities, Octopolis and Octlantis, in Australia, the creatures have built complex cities, complete with their own version of evictions. Within Octopolis, males protect their territories, meticulously etched out to the square meter, by “throwing debris at one another and boxing,” according to Science Alert. In concocting an octopus factory farm, the author of that article argues, we will essentially be engineering an entirely novel octopus culture, one that scales up Octopolis’ “battleground of boxing octopuses” by the thousands. Like other species we’ve domesticated before them, this new society of octopuses will be utterly dependent on us—and we, thus far, have woefully underestimated their labyrinth of both physical and psychological needs.

When you fight factory farming for a living as I have for the better part of 15 years, you spend a lot of time focusing on the most blatant ills: the chopping off of beaks and tails, the forced impregnation, the genetic manipulation for rapid growth. But my research into octopuses has reminded me that for some animals, and especially for cephalopods, the psychological agony we inflict on other animals through confined farming can be even more excruciating than the physical horrors.

Kanaloa Octopus Farm might be small, but its impact on the octopus psyche will run deep.

Beyond its benevolent façade, the farm’s money-making work, at its core, hinges upon controlling the reproductive cycle of female octopuses. At the finale of My Octopus Teacher (SPOILER), I erupted into hysterical sobs as the titular character finally met her destiny: laying her eggs and then fiercely protecting her brood as she withered away without food, encircled by hungry predators. Researchers in 2014 made an astonishing announcement: they’d documented, over the course of 4.5 years, a mother octopus clinging to a rock to protect her growing clutch, all the while rejecting food, before finally perishing.

Without this ultimate sacrifice made by mother octopuses for their young, their species would not continue. And so at Kanaloa, month after month, the team repeatedly induces this always-fatal reproductive stage, within the confines of the farms’ tiny, foreign enclosures and at their own whim, to generate hundreds of thousands of eggs, none of which—as of March of this year—had yet survived into adulthood.

In its quest to crack octopus reproduction, Kanaloa is not only helping to spawn the octopus factory farming industry—it is, like a ship’s sail, a core part of it.

WATCH MY INVESTIGATIVE FOOTAGE

TAKE ACTION

This World Octopus Day, I’m calling on my readers to help turn the tides on octopus farming for good. Take action below:

- Sign this petition to stop octopus farming in the Canary Islands.

- Tweet to the Canary Islands’ tourism agency.

- Share this article on Facebook.