The below story by Hannah Tomes is featured in our first anthology, The Dog Who Wooed at the World. For more powerful stories like this, get your copy!

During the summer of 2022, I made a spontaneous choice that would end up changing my life for the better and introducing a wonderful new member into my family. My dad mentioned that a local organization, which specialized in rescuing abandoned and neglected reptiles, was looking for volunteers. This organization was relatively new to our area, so I had never heard of it before, but I decided to look it up. I have always loved animals and take every opportunity I can get to be around them. At the time, however, I was pretty unfamiliar with reptiles; no one I knew had ever adopted one into their family or had the desire to. Reptile rescues like the one I was about to go to are very uncommon in West Virginia. I thought it would be a fun experience, though, so I went ahead and submitted an application. A week later I was invited to orientation for new volunteers, and from there my journey began.

As weeks passed, I learned more and more about the variety of amazing species I was now surrounded by at the rescue center. I learned that the African bullfrog, Jabba, loved burrowing so far down into the dirt you couldn’t even see him, and he got very cranky if you tried to disturb his naps. I learned that Jonesy the alligator hissed every time someone came close, so it was best to admire him from a distance. I learned that sulcata tortoises could grow up to 100 pounds, but one of them, Opie, was stunted and would never get bigger than the palm of my hand. I learned that Kyle, the bearded dragon, loved basking in the heat and would sometimes get sleepy when you held him.

And I learned that not all snakes were unfriendly after I met Scar, who everyone described as a “scaly puppy” and would rest his head in your hand if you held it out. He’d been severely burned in the past by his heat lamp, which was where he’d gotten his name, but he hadn’t let it destroy his trust in people and he had the sweetest personality.

Every animal at the rescue center had a story. Not all of them were reptiles (there were also a couple prairie dogs, which is a long story), but it felt like we were all a part of one big family, despite our differences. They never turned away an animal in need.

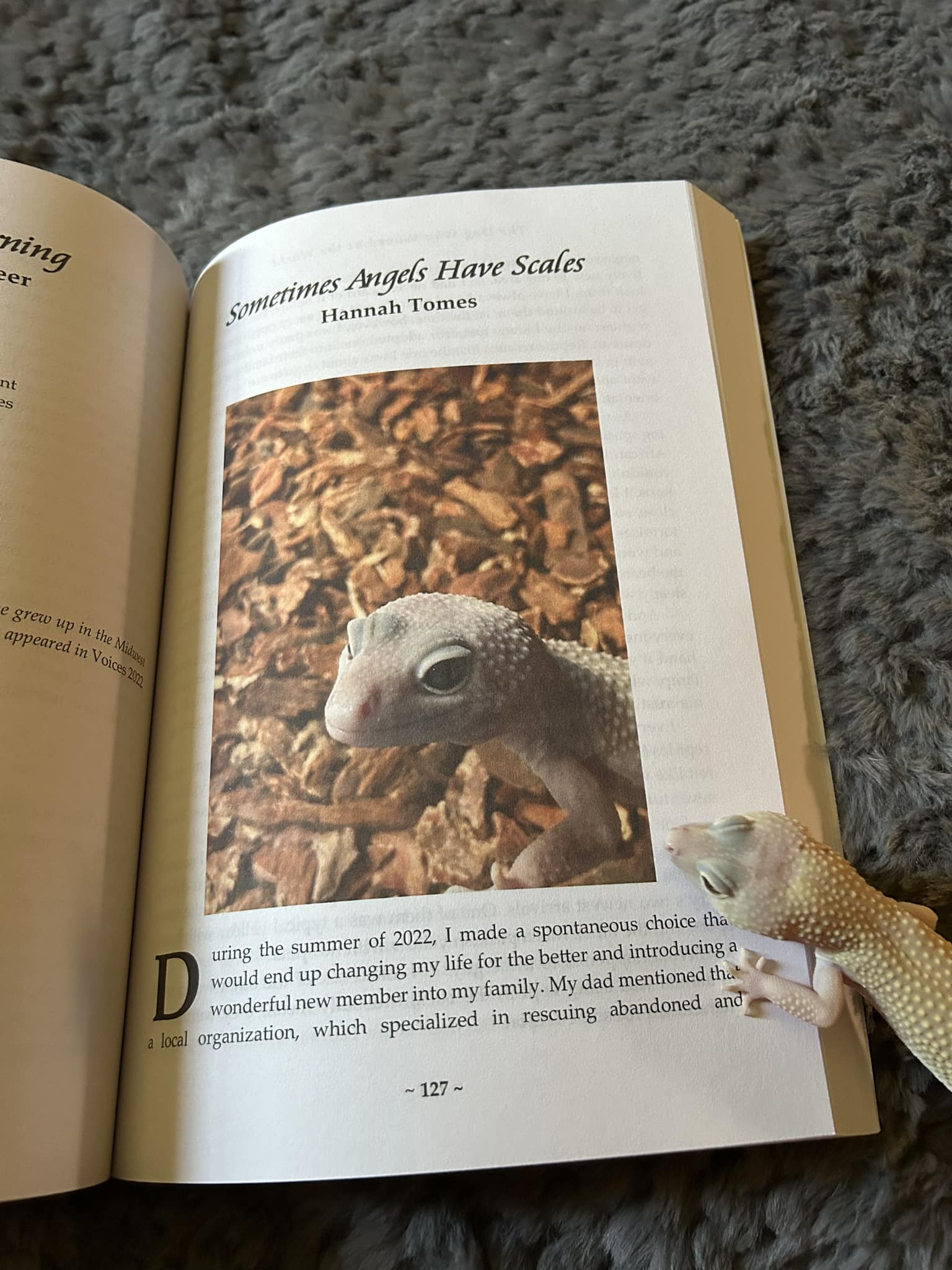

One day later in the summer, I was working in the back when I noticed two 10-gallon tanks sitting on the ground. I went to inspect them closer, and that was when I saw that each one had a leopard gecko in it—the sanctuary’s two newest arrivals. One of them was a typical yellow with black spots, and the other was a pinkish yellow with no spots.

“What happened to these guys?” I asked one of the other workers. If an animal was being kept in the back, it usually meant they were being quarantined for some reason.

“They were brought in last night. Found them in an abandoned apartment.”

“How long had they been there?”

“A few days, maybe a week. No food or water. Not even any heat.”

Hearing that broke my heart, and I watched them for a few minutes. The pink one was sitting calmly on some paper towels, but the spotted one had burrowed underneath and was hiding. I can’t explain it, but in that moment, I felt a connection with that pink gecko, staring up at me with her soulful brown eyes, a little smile on her face. Both of these geckos had been through a terrible situation and it was understandable for them to be frightened, but when I reached into the tank and gently scooped the pink one up, she rested peacefully on my hand, each of her tiny toes pressing softly against my skin. I was fascinated by her. Part of me had feared she might bite me, but she just looked around curiously. I stroked her back with my finger, feeling how bumpy it was.

“Hello, little angel,” I said soothingly.

After I returned her to her tank, I wanted to see if I could somehow comfort the spotted one, but as soon as I removed the lid to their tank, they chirped with fear and burrowed farther into their paper towels. It was strange, I thought. Despite being abandoned and probably dealing with some abuse before that, the pink one was so friendly and trusting. It was like she just wanted love. Once it was determined that both the geckos were healthy, they were put up for adoption. The spotted one was adopted quickly, but the pink one remained. When I visited each week, I went straight to the back room, where I would greet her.

“Hello, my little angel,” I would say every time. When I looked at her, I was overcome with emotion. How could someone so innocent, so precious, not have been adopted yet? Surely she would have a home soon. As weeks passed, a new thought occurred to me, something I never would have thought possible before. What if I adopted her? I had never been a reptile’s guardian before. I’d just had what were considered “normal” companion animals, like dogs, cats, and hamsters.

During my time at the rescue center, I’d learned about what was required for leopard gecko care. But was I capable of doing it? I began doing some research. I knew it was a huge responsibility, and I didn’t want to bring the gecko home unless I was certain I could provide her with the right environment. For a while, there was one thing holding me back: they ate bugs! They had to be live bugs, too, because many small reptiles will only eat moving insects; they cannot be successfully fed pellets. At the time, it was hard to imagine buying and keeping live bugs for my gecko. It was too gross, I wouldn’t be able to do it, and yes, it is sad that insects have to suffer for lizards to eat—but I couldn’t ignore the way this gecko was tugging at my heart. One day I thought to myself: what if everyone who ever considered adopting a reptile let this stop them? Sometimes in life, getting out of your comfort zone is worth it.

As the summer came to an end, it became clear to me that I had a choice to make. My family and I were going out of town, and while we were gone, there was going to be a reptile expo. The rescue center always took their animals to such events and would try to get people to adopt as many as they could. I decided that when we came back, if the gecko hadn’t been adopted at the expo, it would be a sign that she and I were meant to be together. I thought about it for a few days, looking at photos of that endearing face that I had taken on my phone, photos of that little angel sitting on my hand so casually, like we had known each other forever. When we returned home and I went back to the rescue center, I was preparing to be disappointed. I stopped to talk with some of the workers about the expo before heading to the back.

“It went great. We got all of the animals adopted,” one of them told me. “All of them except the gecko.”

My heart soared. What were the odds? It was meant to be, I was positive now. I practically ran back there, and there she was, waiting for me in her tank with a smile. I spoke with the owner of the rescue center immediately, and we worked out the adoption. I am very grateful to him for helping me get all of the supplies I needed and recommending what would be best. By late August, it was time for me to bring the gecko home. But there was one thing I wanted to know. All of this time, I hadn’t even known if she was a boy or a girl. The owner examined her, and he told me she was a girl. A little girl. I already knew what I was going to name her. Angel.

Once Angel was home and I had everything set up for her, I couldn’t believe it had actually happened. I had a companion leopard gecko! I was so excited to share the news with all of my friends and family. There were some mixed reactions (a lot of people aren’t too fond of reptiles, as I’ve come to find out), but overall, everyone was happy for me. It’s hard to believe months have passed already, and she’s settled into her new home wonderfully. I am so glad I decided to try something new—something a little scary—because I have gained such an adorable addition to the family, and she has been the sweetest companion. I also overcame my reservations about handling bugs!

I’ll never forget the day I met Angel and what she went through. Even though she had to deal with extreme trauma, she was not afraid to put her trust in me and warmed up to me almost instantly. I couldn’t understand why no one wanted to adopt her before I did, but perhaps they just didn’t have the connection with her that I had felt from day one.

Now I know she will be safe and loved for the rest of her life, and I am so thankful that she came into mine. She taught me that all animals deserve a chance, even if they’re not furry and cuddly. They can have a bond with humans that’s just as close, if not closer. I’ve never seen an animal that responds to my voice the way she does. The way she gets so alert and raises her head to hear me better. How she closes her eyes halfway, as if the sound is like beautiful music. My relationship with her has changed me for the better and ignited a passion in me for reptile conservation, as they are so often overlooked.

People always say that dogs are the angels we have here on Earth, and though I agree, I think sometimes reptiles can be angels in disguise, too.

🦎

Hannah Tomes is a college student studying Professional Writing. She lives in West Virginia with her dog, a black lab named Jade; her cat, a Russian blue named Cloudy; and the newest member of her family, a leopard gecko named Angel. She has always adored animals and is currently a volunteer at a local organization that takes in abandoned and neglected reptiles.

For more inspiring stories of courageous animals, get your copy of the anthology today!