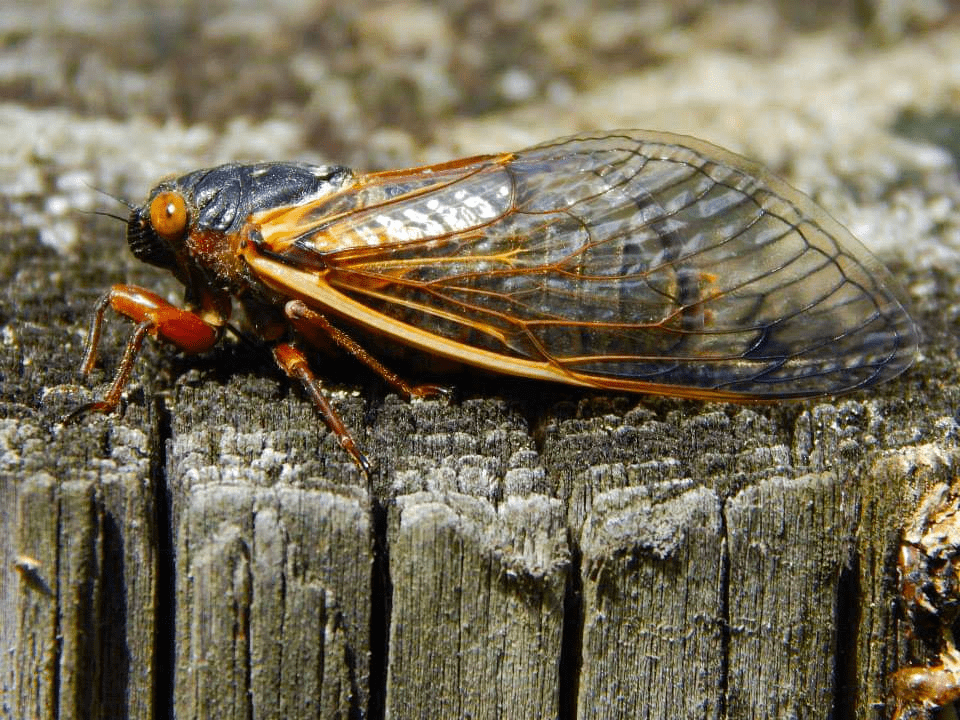

It’s a sizzling afternoon in the summer of 2013 in the suburbs of Virginia, and the air is filled with shrieks. An insect flutters to the ground, nearly colliding with my head. As she perches on a nearby tree stump, I capture her silhouette on camera, the intersecting orange lines of her wings against her jet-black body. To the screaming children at the park playground, she’s a menace. To me, it’s like the earth has opened up to deliver a marvel that has been hidden right under our feet for the last 17 years: the cicadas of Brood II.

To this day, I’ve been fascinated by cicadas—their love songs in the afternoon, their alien-like faces, the skins they leave behind that, as a child, I plucked from the trees and stuck to my own t-shirt like Velcro to show off to my friends.

I eagerly awaited the arrival of the cicadas each summer, growing up in Richmond, Virginia, and their songs became my lullaby. Memories of eating ice cream at dusk in flip flops are punctuated by the soundtrack of the singing insects. As an adult, instead of counting sheep, I often play cicada sounds on Alexa to soothe me to sleep. They’ve always been a reliable constant, a reminder of the days when stress from schoolwork faded into endless daytimes, barefoot adventures, and magical forts in the woods.

But In 2013, when I was 25, I met Brood II, the East Coast brood that arrives every 17 years, for the first time, at least that I can remember with clarity. Their last appearance, in 1996, had been when I was merely eight, a tumultuous year that served as my introduction to death and loss: first, it was my beloved family dog and protector, Wookie, and then, I met the savage and swift glioblastoma that consumed my grandfather’s brain and expunged him from my life for good. Had I crossed paths with Brood II that summer, their memory would have been as temporary in my mind as their aboveground lives had been.

But in 2013, when hundreds of millions of insects flooded the sky, the trees, the roads, and basically every orifice of nature once more, I arrived to the spectacle with open eyes. They flew through car windows, got smashed in the streets, were consumed by dogs, and invited themselves to cookouts like that nosy neighbor who doesn’t know when to leave. They were no longer a soft, warm friend. They were here, they were louder than ever—and I loved every minute of it.

That summer, I dove into learning everything I could about these faerie-like beings and the groups of “broods” that appear at different intervals in different regions of the country. Annual cicadas were always a soothing accompaniment to summer, predictable, reliable, steady. But periodical cicadas like Brood II—they were rare, bold, fleeting. They descended on humanity like a meteor, and then vanished just as quickly. They were “Dust in the Wind,” as Kansas says, and that made them a spectacle to behold.

In August of 2013, while America embarked on back-to-school shopping and end-of-summer soirees, Brood II vanished right on schedule. And just like after the departure of my grandfather so many years before, I continued on.

By the time the summer of 2021 touched down, I was 33, living alone with my dog and pig in the foothills of the Shenandoah mountains in a new town that was home to yet another periodical cicada, Brood X. What seemed like a lifetime had transpired since I last came face to face with Brood II, the only periodical cicada that ever emerged in my hometown of Richmond. I’d fallen in and out and in and out (and in and out) of love, gotten divorced, moved at least four times, watched death steal even more loved ones, grew bonds with dogs and pigs who captured my heart, navigated isolation during a global pandemic. I’d raged; I’d spent time holing up inside myself; I’d become weathered.

But I never forgot them, the cicadas of Brood II. And in 2021, I frothed with excitement as the headlines started popping up about the impending the arrival of their cousins in Brood X, overflowing with cicada recipes and spawning cicada memes. In those first few days, my ears perked up at the sound of faraway sirens. It was as though an alarm was malfunctioning at the nearby hospital. But it grew closer, and closer, and closer. As it did, I became antsy and began to steal glimpses of those insects I’d accidentally discovered in the earth while doing yardwork. I’d lift a rock and find them hovering, waiting in their tiny round holes in the ground for their cue. Finally, one of them, who had a nose like Q*Bert’s (and whom I had named, simply, George), finally ascended my nearby fig tree, to my delight. By the end of the first week, my yard had seemingly morphed into cicada HQ.

One evening, camera in one hand and flashlight in the other, I set off into the dark. Immediately, I caught sight of a cicada on my left whose needle-like legs were clasped tightly to the blue paint on my house. His exoskeleton was frozen delicately in place, as his tender, cream-colored body emerged from within at a glacial pace. My flashlight illuminated his vivid yellow, newborn wings, unfurling into the pitch-black night. His red eyes seemed to glare back at me like an ambulance’s lights.

In my encounters with Brood II almost a decade earlier, or with the many annual cicadas, I had never seen this exact moment of birth—not of a new life, but of life in a new place, in my place. Silently, undetected, these creatures crawl beneath our feet for nearly two decades, experiencing a world we never will. They tunnel through thick dirt, passing earthworms and grubs, with no need for vision, for the set of five senses that define our lives. Those 17 years comprise 99 percent of their lives; above-ground, they exist for mere weeks. What we see—their crisp, shining wings—and what we hear—their piercing cries—actually, then, are the beginnings of their deaths.

That night I got a glimpse into their hour of transfiguration. For 17 years, as we drive to and from work, journey from city to city, walk our dogs and ride our bikes on the sidewalk, they are just underneath us, excavating, sucking on tree sap, burrowing. Then, on that seventeenth year, they lie in wait for the day that the temperature of the earth reaches 64 degrees. As the sun sets, the grub-like nymphs begin their ascent. With their hooked front legs, they dig through the top layer of soil, thrust themselves onto the land, and begin to scale the nearest tree (or, today, fence, house, or other structure). Once lodged in a comfortable position, in the dead of night, the process begins: a slit forms along their backs and slowly, the adult cicadas’ pale, delicate, soft bodies extract themselves from their former skin. In the hours that follow, the cicadas sit motionless as their crumpled-up wings miraculously unfold and harden into tools that will lift them high into the trees come morning. In one night, as we sleep, millions of formerly beetle-like nymphs have taken to the skies like tiny, glittery birds.

I began to walk the perimeter of my fence and saw dozens, then hundreds, of tiny insects dotting the wooden panels. I approached a cicada who sat silently adjacent to her once-protective skin that encapsulated her through her sightless journey underground, encased by mud. This was her first night in the open air, filled with the aromas of freshly cut grass. My flashlight was her first time seeing light in her 17 years of life. That night, her new skin would harden and turn from cream to black, preparing her for a whole new life aboveground.

A short life, already stamped with an expiration date. As I snapped her photo, the novelty we both witnessed—me, meeting a tiny backyard alien, and her, breathing in open air—lasted only seconds. I would persist into August, while she would soon succumb to old age and gracefully fall from the forest canopy, if not first devoured by a hungry bird, dog, or pig.

Yes, a pig—specifically, the 100-pound potbellied pig inhabiting my home who quite quickly and gleefully developed his own cicada transfixion.

Early into my 2021 Brood X festivities, when it was time to turn off the lights and head to bed, Peppercorn the pig was not nestled into his pod (the dog bed topped with a comforter topped with an old beanbag chair into which he burrows/disappears at night). I called for him outside, and I heard nothing. After a moment, I located him in the far corner of the fenced yard, munching on something crunchy. As I approached him, commanding him to return to bed, he began running along the fenceline away from me, grabbing bites of treats all the while.

To Pepper, the earth had apparently gifted him with an endless supply of Ferraro Rocher truffles. I gaped in horror.

Once I finally corralled the pig into the house and covered the flap of his pig door, I realized the battle had just begun. He paced back and forth in front of the door, nudging it with his nose and squealing. It was as though he’d not been fed for weeks. He was obsessed. I resorted to sleeping in front of the door to keep him at bay until he finally wore out and went back to the pod for the night.

Thus commenced a monthlong, fruitless endeavor to save every cicada. At night, before a new batch of them broke through the soil and journeyed up the fence to commence their molt that would enable them to retreat to the trees, I’d close up Pepper’s pig door. Then, before he was due to relieve himself at bedtime, I’d head out with my flashlight and patrol the fence, moving every climbing cicada to the other side of the fence, away from Pepper’s wrath. Only then, after this 30-minute ritual, would he be allowed outside.

In the morning, back around the fence I would go, relocating any still-hardening new cicadas from the lower to upper parts of the fence, where they were out of reach of my determined pig.

Like Pepper, I’d become obsessed. While he was intent upon devouring as many cicada candies as could fit in his belly, I was intent upon rescuing just as many. After all, I reasoned: they’d spent 17 years tunneling underground, never seeing the light of day, preparing for this culminating moment. Their final mission in life was to sing into the summer air, woo their soulmate, deposit approximately 500 babies into a tree branch to carry on the species, and then go out with glory. The future of Brood X depended on these very cicadas to survive and continue the cycle.

Yet, as soon as they reached their destination, Pepper was there with a toothy grin to abort their mission.

One Thursday afternoon, I finally brought up to my therapist, a fellow animal lover, the ongoing distress and drain on my internal resources that the Brood X debacle was causing me. I expected a wave of empathy, but instead I got a chortle.

It was not, however, because she was among the millions of Americans who found the cicadas to be, at best, a loud annoyance, and, at worst, an all-out invasion on our senses. On the contrary, she truly empathized with these miniature sirens, valuing them for who they were.

Who they were—not who they weren’t.

They were a species that had evolved over eons to swarm the earth in massive numbers every 17 years, leaving virtually no remaining members protected and safe underground. Their ongoing survival depended not on the individual, but on the hoards. It was as though a certain mortality rate was baked into their DNA—only the lucky will ultimately survive long enough to reproduce. Owing to their apparently delicious flavor profile (according to Pepper), most would become snacks for ravenous carnivores, or victims of car crashes and other collisions.

But they were not me. When peering into the sunlight for the first time, perhaps they felt warmth; perhaps they, too, felt wonder. But perhaps they did not plot out their mating mission, like a single 20-something creating a dating profile and ranking potential suiters according to compatibility and alignment with their lifelong goals. Perhaps their goal was simply to reach the nearest tree and sing. Or perhaps they did not have goals, at least in the way I envisioned them.

Perhaps, the 17 years leading up to that culminating summer were the true voyage, invisible to us yet teeming with adventure: charting out new root systems, bumping into fleshy worms, getting acquainted with their peers, plotting their territories. Perhaps, then, in our world of yellow sunshine, high-speed internet, and automobiles, they are like an elderly woman in her rocking chair, sighing a final satisfied breath. They are ready.

Yes, their extermination by a hungry pig was unfortunate; my sadness, I decided, was justified. But my anthropomorphizing of these mystical creatures with bulging eyes had derailed my life as I sought to preserve them in the same way I’d rescue a cat from in front of a car or a chicken who’d fallen off a slaughter-bound truck. Unlike cicadas, cats and chickens aren’t popping up from between blades of grass by the trillions and overwhelming the landscape so that a sufficient fraction will survive to carry on their species’ legacy. If they did, the animal lovers among us would have an unprecedented ethical quandary on our hands.

As someone who cannot turn her back on an animal in need, ever—I actually stopped my car about 11 times along a drive down dark country roads this past March to move toads out of harm’s way—relinquishing control and facing the reality that I could not save every cicada was rough. Not patrolling the fence felt irresponsible. If a life could be spared, shouldn’t it be?

But the mortality of the cicadas was way beyond me, or any of us. It was a universal inevitability. I was whisking them from Pepper’s tusks knowing full well that by summer’s end, they’d be long gone. “Dust in the Wind” echoed in my mind.

So, with all my might, I stopped—well, almost. I still kept Pepper indoors during cicada primetime. And I decided that if I could not save them all, I could save a few. When I came along those who, without my assistance, would surely wither away, I stepped in: I took in two cicadas with wings that hadn’t quite unfurled and had hardened into a twisted shape, rendering them unable to fly, and hence to mate, and to have a chance to help carry on their species at all.

I named my two rescues Nick and June (Handmaid’s Tale, anyone?), and for two weeks, I brought them fresh tree branches each day in a large glass jar inside my kitchen and watched them climb and eat, and climb and eat. The heaviness of the countless fatalities, the smashed cicadas in the roadways and those picked from the trees by crows, faded away as I observed Nick and June thrive.

Then, one day, as I was cooking spaghetti, June withdrew her ovipositor and began laying her eggs, hundreds of them, into a branch. I filmed her, marveling at the life cycle playing out before my eyes.

Then, of course, she died. Nick went with her; it was rather “Romeo and Juliet” of them. Like that of the octopus—a wonderfully complex animal oozing with intelligence and skills and adaptations who ultimately perishes after creating new life for the very first time—the plight of the cicadas felt unfair. A remarkable existence tied to a ticking clock.

But it was the only way it could be, according to whatever laws govern our world and our universe, and there was no surmounting it. Spending hours monitoring the fence would not stop it. And, obviously, caring for this betrothed pair with crumpled wings wouldn’t either, although it provided the relief I needed in that moment to grapple with that immense powerless. That relief, that settling of inner turmoil, means something to a human wrestling with insurmountable existential dread. I cannot end death, the shadow that has clung to my heels a little too tightly in recent seasons. But the knowing that I had helped, in some way, in the only way I could, mattered.

A few weeks later, I went out and tied the egg-filled branch into a bush to allow these new cicada-lings to crawl into the earth, not to be seen again by humans until 2038. That summer, I’ll be freshly 50. Presumably, I will no longer live in these mountains, or even in this state, to greet these young teenagers as they come up for their brief and only season of lovemaking. By then, I will have loved, and lost, many more beings, friends, and family, compounding the recent losses I’ve endured—my soul dog Powder, my second mom Sherrie, my aunt, my father’s near-death experiences—and by then, perhaps I will have inched slightly closer to accepting the inevitable mortality of myself and everyone I know. Today, in 2022, I face the looming threat of death like a terror greater than skydiving, or tightrope-walking, even as the losses pile up around me.

But Nick and June the cicadas brought me some semblance of control, of seizing the steering wheel on the train called mortality that every living behind rides. Yet, a final reminder that permanence and immortality are still far beyond my reach hit me as I was readying this story for publication. I was searching high and low, but ultimately came up empty, for the footage I had taken of June laying her precious eggs last year. Apparently, it was one of the many victims of a phone hacking incident I faced last summer. Now, the evidence of her final deed exists only as specks in my memory—and, hopefully, in hundreds of baby cicadas who will be digging invisibly around my yard for 16 more years.

Today, when I strum Kansas’ “Dust in the Wind” on my ukulele, singing, “Don’t hang on; nothing lasts forever but the earth and sky,” I think fondly of June, Nick, and their babies. And I remind myself that cicadas are not us, and we are not them. But in their deaths, I have learned about my own. And their beautiful overnight transfiguration, from hidden nymph to shimmering wings in the summer sky, and their utter transience in our aboveground world—that’s precisely what makes them magical.

If I’m lucky, this summer, I’ll get a peek of the stragglers of Brood X, the few who opted out of last year’s rendezvous in favor of one more year of tunneling and drinking sap, as they hit the skies as 18-year-olds, ready to go out with a bang.

Special thank you to Tina Marie Johnson of Blue Mountain Poetry Salon for the exceptional writing coaching that guided me through the creation of this piece.